Deep Dive 4

Pacific Ocean Expedition Blog

Live updates from the team aboard Pressure Drop during the mission to dive to the deepest point in the Pacific Ocean – Challenger Deep.

MISSION COMPLETE: May 2019

MISSION COMPLETE

We sign off now, our historic mission to the Mariana Trench and two of its Deeps complete. It is almost unreal to have dived five times, with no aborts, to such extreme depths but we did indeed do it. I remain so incredibly proud of the team and the sub they built, maintained, and sustained.

Many of us head home for three weeks to rest and recharge before we tackle perhaps the second-deepest trench in the Pacific, the Tonga Trench, while others will remain on the sand science-collection hip to map and conduct science missions in the Solomon Islands on the way down. The research never stops.

Until Tonga . . .

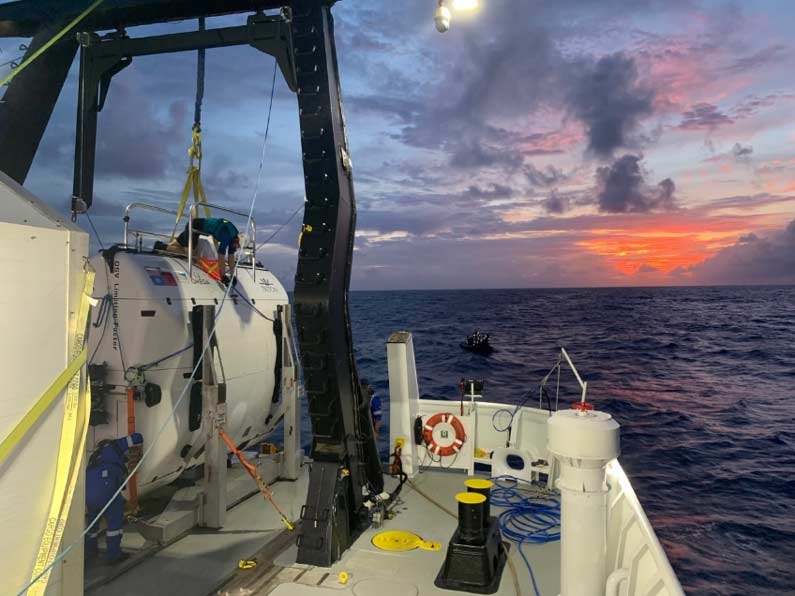

The hangar area of the DSSV Pressure Drop, waiting for the Limiting Factor to come back up during Dive #2 to the bottom of the Challenger Deep. And yes, the sunsets were that beautiful during this dive series. This was not photoshopped.

BACK IN GUAM

It was an interesting 48 hours trying to get back into Guam. Even though we were in the port just twelve days ago, we were actually denied entry because we didn’t have an approved and US Coast Guard-stamped “Vessel Response Plan for accidental oil discharge” specific to Guam. I certainly understand the importance of regulations to safeguard American waters from contamination, but it did strike us all as a bit of classic, Kafka-esque, sentenced-to-purgatory-by-red-tape moment.

Our vessel was perfectly safe to (re-) enter the port of Guam, but we didn’t have the proper stamp to allow it. Thus, we anchored 12.2 nautical miles offshore (outside of territorial waters under threat of a fine of $91,000 per person and a Class D felony for our captain if we dared to breach the 12-mile line) until we received the proper permit.

Without going into too many details, some friends of the expedition took up our cause and were able to facilitate our permit application getting reviewed on an expedited basis (which is allowed) and get it approved. After about 36 hours sitting at anchor, we were given the green light to dock in Guam. Everyone involved was very polite and just following the rules but good gracious, it was a bit frustrating after the intense operations and accomplishments of the last two weeks.

So much waiting for such a small piece of paper . . . but eventually, we got it properly approved and were able to re-dock in Guam.

GUAM BOUND

Our time at the Mariana Trench is at an end. We could stay here longer and continue diving if we desired, but we have a schedule to keep in order to visit the Tonga Trench, Puerto Rico again, and eventually the last of the Five Deeps, the Molloy in the Arctic. The “limiting factor” of our continued full ocean depth dives is not the submersible, but rather our own provisions onboard and limited time before our next destination. We could have dived to full ocean depth every day if we had wanted to and staffed up for it. The submersible has proven itself that strong and reliable. It really is an extraordinary piece of engineering and the team does a fantastic job maintaining it.

For now, though, we are cracking open a few bottles of Champagne, having an al frescodinner on the top deck of the ship, and are enjoying each others’ company as we sail back to Guam. This team of 48 individuals on board has been forged over time into a great team and achieved something never accomplished before– or even attempted: five dives to full ocean depth in ten days, and five people to those depths as well. If one includes the Sirena Deep – which I would because 10,700 meters is pretty much full ocean depth –we more than doubled the number of dives, and people to the bottom of the ocean, than in the past 59 years combined. I am thankful to have had the opportunity to work with a group so gifted and hard-working for the benefit of technology, science, and yes, even plain-old adventure.

The sunset that greeted us as we celebrated a safe and successful cruise to the Mariana Trench. The weather certainly smiled on us this voyage, for which we are very thankful.

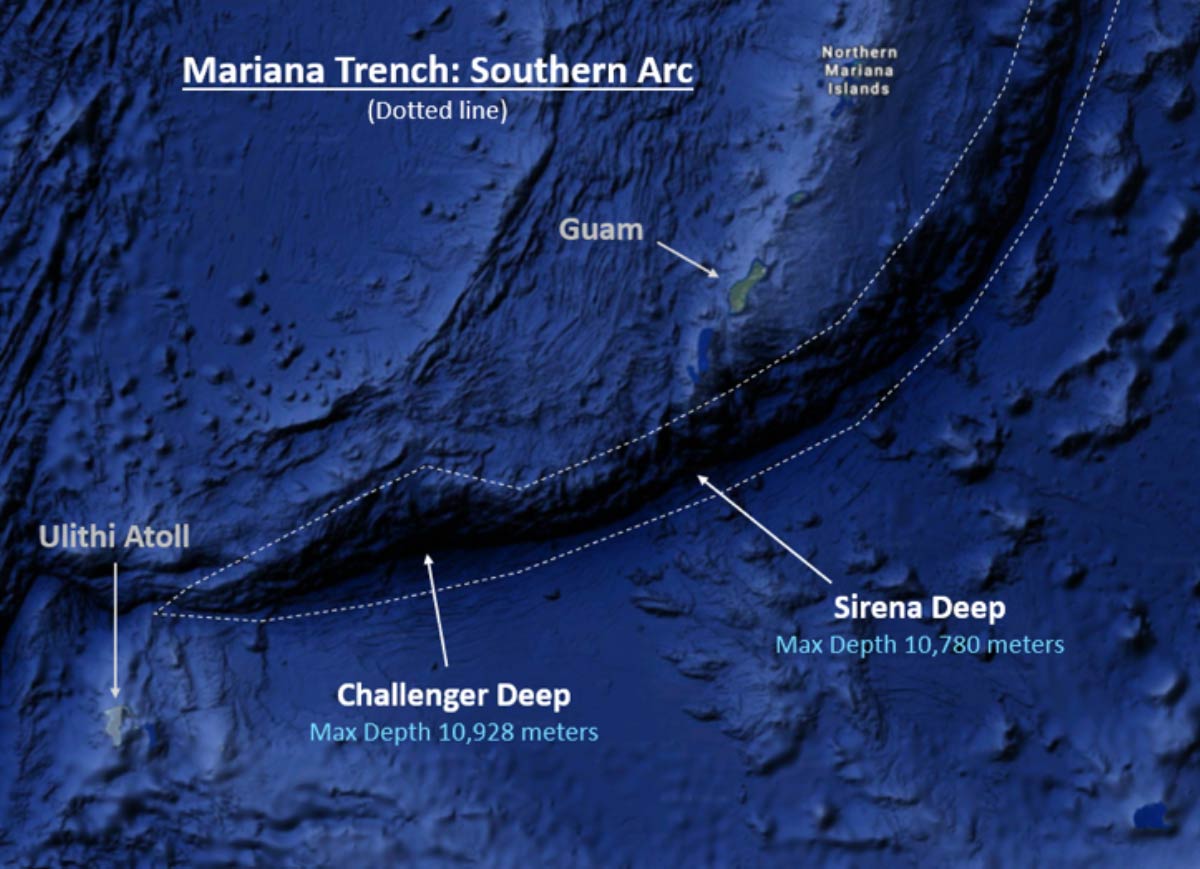

THE SIRENA DEEP

The Challenger Deep gets an enormous amount of attention because it is the deepest place in the world. However, the Sirena Deep is almost as deep – less than 130 meters shallower – and potentially of even greater scientific interest based on the opinions of some scientists. It is very important to the members of our expedition that our journey is not just one of adventure or technical achievement, but also of real scientific value. Therefore, we took guidance from the scientific community and invested the time to make not another dive in the Challenger to try and break more records, but to try and find something new and interesting of pure scientific value in the Sirena.

Which we think we did.

Dr. Jamieson and I spent just short of three hours on the bottom of the Sirena cruising above the seafloor along boulder fields at 10,700 – 10,300 meters. We saw rocks with unusual colors like red, yellow, and even orange which appeared indicative of “bacterial mats” and even serpentization at these extreme depths. The things we saw and filmed, for hours, we believe will help scientists understand non-photosynthesis-based organic reactions and life development that is outside the norm of regular human experience. Both Drs. Jamieson and Fryer, our senior onboard science team for this expedition, were “very excited” by what we found. In particular, Dr. Fryer was ecstatic that we were able to retrieve some rock samples from the bottom of the Deep — not through the use of the manipulator – but by me accidentally bumping into some large rocks and having parts of them shear off and serendipitously deposit themselves in different recesses of the submersibles under-structure which were carefully retrieved later. To echo Dr. Jamieson, “It was a good day for science.”

Dr. Alan Jamieson, Newcastle University, boarding the Limiting Factor for his second dive below 7,000 meters in the sub. Just weeks earlier, we dove the Java Trench together.

Dr. Alan Jamieson and I in the Limiting Factor at the bottom of the Sirena Deep (10,700m). The first manned descent to that Deep in history.

Tim once again “riding the bull” (the Limiting Factor) as it is towed back towards the Pressure Drop for recovery. After six months, we feel we have perfected the launch and recovery of the sub after some initial challenges.

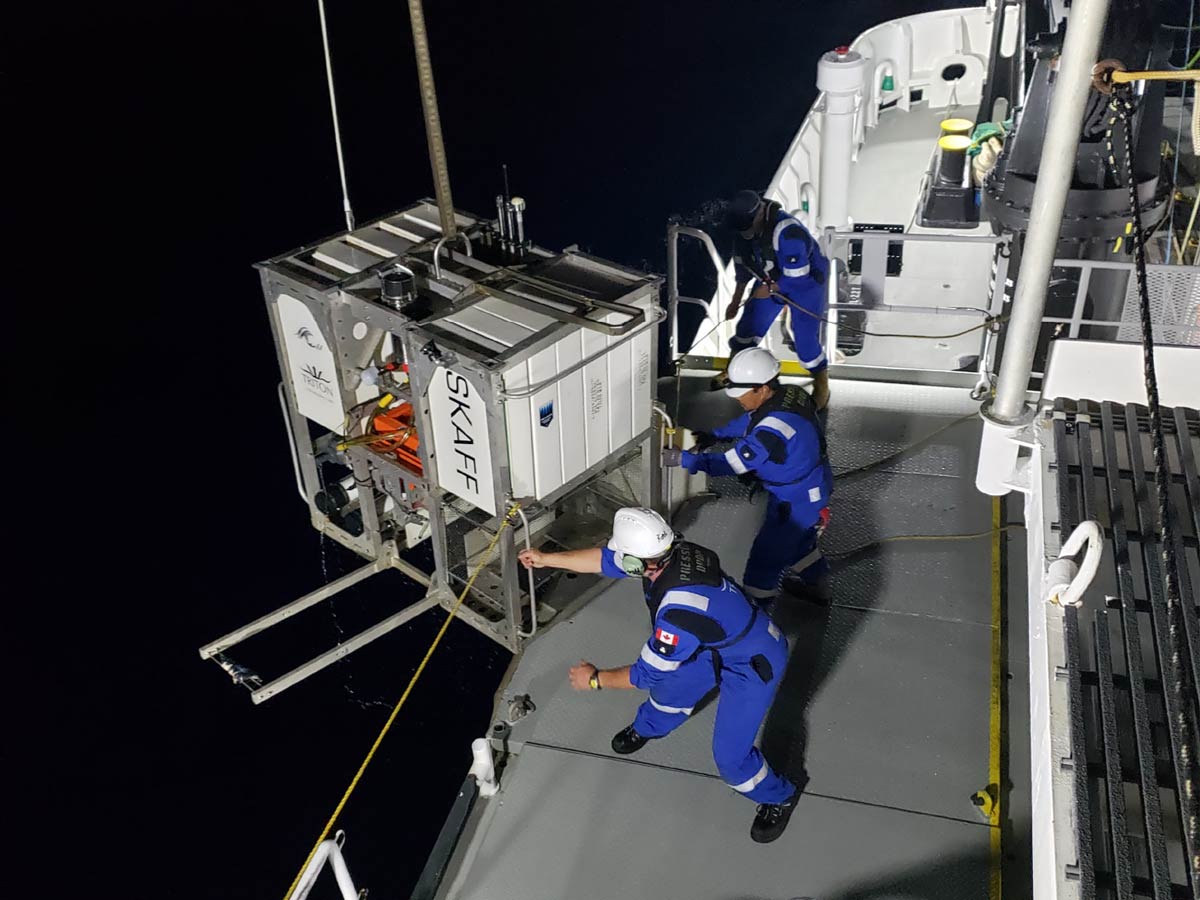

The absolutely stellar and expert launch and recovery team from Triton Submarines. There are none better. That is probably two centuries of deep submersible or professional diving experience in that photo.

MOVING EAST.

After making four dives in seven days to the bottom of the Challenger Deep, we are heading east to focus even more on science – to the Sirena Deep about 128 miles away. This transit also allows us to rest the crew and carefully maintain the Limiting Factor, in particular the manipulator arm that had a bit of a fit the previous day. We will identify the vulnerable point in the device that caused a problem, and reinforce it if we can. This is part and parcel of building the first full ocean depth vehicle and taking it up and down the water column multiple times quickly. I can’t think of many, if any, mechanical devices that have been repeatedly stressed four times in eight days to 16,000 psi – back and forth, in saltwater, and residing at that pressure for 3-4 hours at a time – in just seven days. One is going to have a few issues but we use these events to make the sub’s components stronger for future dives.

Drs. Jamieson and Fryer are studying the historical data on the Sirena carefully and we are deciding today where to place the landers and sub for maximum potential scientific gain. We understand there might be some very interesting biology down there based on James Cameron’s expedition in 2012 which placed a lander on the Sirena, and like good scientists, we hope to build on that experience.

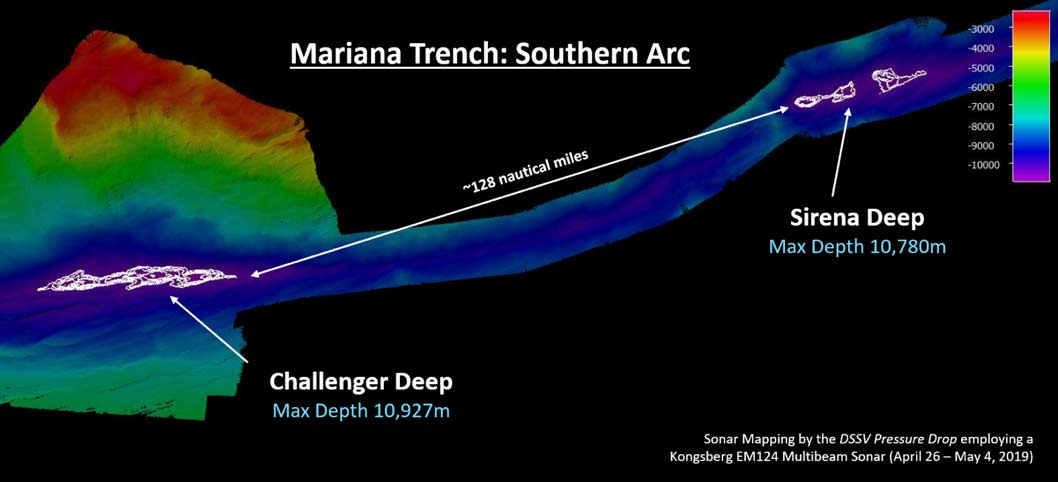

A map showing where the never-visited Sirena Deep is in relation to the Challenger Deep. They are both very much part of the Mariana Trench, just different “Deeps” within it. At approximately 10,780 meters deep, the Sirena Deep is usually considered a “full ocean depth” dive.

“COMMONWEALTH” DIVING DAY.

Success #4!

Today we completed our fourth dive at the Challenger Deep in eight days, the so-called “Triton Dive,” with Patrick and John onboard. I sometimes referred to it myself as “Empire” day because Patrick is (very) Canadian and John is (very) English – so since they are both members of the former British Empire, it fit. We were all quite excited because the Challenger Deep was itself named after the HMS Challenger, a British research vessel, which discovered the trench in 1875 and John Ramsay is now the first Englishman and British citizen to dive to the bottom of the Deep. With this dive, he also eclipsed the diving record the expedition recently set for a British citizen (Dr. Alan Jamieson, a Scot) at the Java Trench just a month ago. Patrick made his second dive to the bottom of the Challenger Deep as well.

The main scientific objective of the dive was to collect some rocks from the Central basin of the Deep, but unfortunately the manipulator didn’t work on our fourth (and fifth, final dive) in the Mariana Trench. We believe insufficient compensation pressure allowed seawater into the electrical portion of the arm, which resulted in the loss of the wrist yaw, jaw rotate and jaw open and close functions. We are now working closely with the manufacturer to correct these faults ahead of the next dives in the Tongan Trench. Oh well, this is often an iterative process to get everything right.

The two aquanauts did, however, survey the Central Pool for well over a kilometer on a three-hour dive. High-definition cameras followed them the whole way and two landers, Skaff and Closp, were down there with them as well. Skaff seemed completely unintimidated to go right back down after his prior mishap at the bottom. We will be reviewing what they collected over coming days and weeks to see if there are any interesting scientific findings.

John Ramsay (of Devon, England), the principal submersible designer, preparing to enter the Limiting Factor for his first dive in it ever – and he would be going to the bottom of the Challenger Deep. Talk about a heck of an inaugural dive in your own creation . . . He is now the deepest diving Briton/Englishman in history.

The Limiting Factor, with Patrick Lahey in the pilot’s station and principal sub designer John Ramsay next to him, descends to the Challenger Deep – again – for the fourth time. The Zodiac boat Xeno. keeps station nearby to ensure a safe launch.

The Limiting Factor being brought back on board after diving to the “Central Pool” of the Challenger Deep. Given the sheer length of the dives to the bottom of the Deep, we typically launched at 8 am and recovered 11 hours later around 7 pm.

Me, not in my diving flight suit for once during a dive. It is quite difficult for me to watch others get into the sub to “fly” it on a mission to FOD. In the control room, others compared me to a “pacing leopard in a cage” when the sub was underwater.

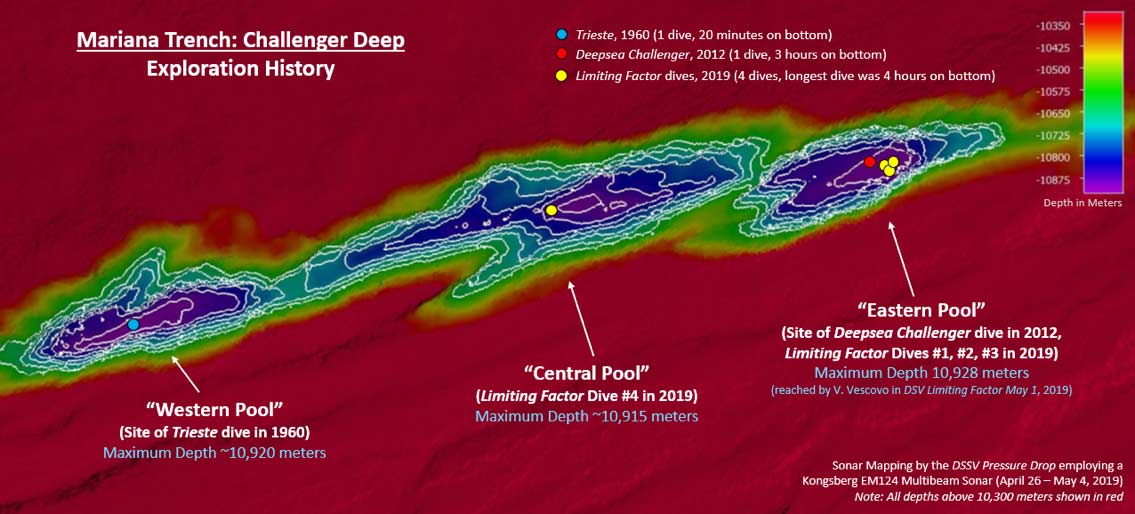

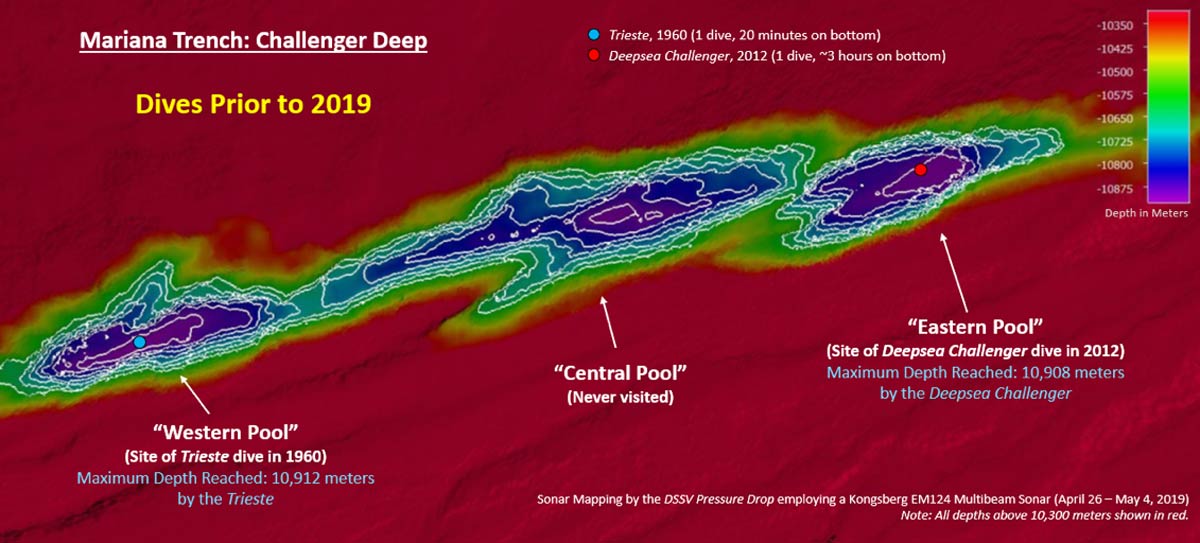

A summary of the historical dives and the ones made by the Five Deeps Expedition. We did not dive the “Western Pool” due to the presence of an underwater buoy left there by Dutch scientists that posed an entanglement hazard. We were told it has a 2 kilometer tether, and we wanted to stay well clear of that.

REST & RELOAD.

We are being careful out here and taking a full day to rest and refit the sub and landers after every dive. We have the ability, if we had maybe two more sub technicians for a night shift, to dive the sub – even to full ocean depth – every daybut we didn’t feel the need to press to that tempo. Instead, we are deliberately checking the sub, letting people rest, and planning for another dive — #4 in 8 days —tomorrow.

As part of my overall building agreement with Triton Submarines who of course designed and built the Limiting Factor, I agreed long ago to let them have one dive at the Challenger Deep if we ever made it this far. Tomorrow will be the day for that dive and Triton decided that Patrick would pilot the sub and take down John Ramsay, the sub’s structural designer and an Englishman from Devon. They would have a definite science mission, however, which will be to dive in the “Central Pool” of the Challenger Deep, explore the south and north subduction areas, and hopefully collect some rocks for Dr. Fryer – the marine “trench expert” we have on board for this dive series. This would be the first ever dive to the “Central Pool” of the Challenger Deep.

Dr. Fryer hopes that we are able to recover the first rocks ever retrieved from the Challenger Deep to help substantiate her theory that there is a separate, small tectonic plate in the area that is different than the main plates. If true, it could help us further refine our understanding of plate movements and their effect on surface phenomena and natural disasters like earthquakes and tsunamis.

Cassie Bongiovanni, the Expedition’s Sonar and Mapping leader, discussing the Challenger Deep dive sites using our Kongsberg EM124 sonar with Tomer Ketter of Israel, another of our GEBCO-trained hydrographers. Their next mission is to identify precise dive sites in the “Central Pool” of the Challenger Deep and later, the Sirena Deep.

SALVAGE DIVE.

Today we accomplished what has to be the deepest marine salvage operation ever!

Patrick Lahey and Jonathan Struwe (of maritime classification firm DNV GL) dove in the Limiting Factor – for the third time in just six days, to find Skaff. On the way down, we discovered that Skaff’s batteries actually held out longer than expected and we received a single “ping” from him informing us that Closp was within 100-200 meters of him, which really boosted our confidence in being able to find him. It almost seemed like a single plaintive cry for help from the lander who had been trapped in the dark at the bottom of the world for 2.5 days.

After initially vectoring towards a rendez-vous with lander Closp who had been sent ahead earlier , the team was able to find Skaff on the bottom with the sub’s sonar and maneuvered towards him. Once they found him, they carefully extended the sub’s manipulator arm, gave Skaff a good shove, and he escaped from the mud he had sunk into and began ascending to the surface! A big cheer went up in the control room when we heard this. Five hours later, the sub, Patrick and John, and both landers were all on the ship and we were back to full strength with all landers. It was an amazing mission at the very bottom of the ocean. We don’t think it is even possible to have a deeper salvage mission because Skaff was pretty much at the Deep’s deepest point.

A nice side benefit of the dive is that it demonstrated to Jonathan and DNV GL the safety and capabilities of the sub, and he granted us full commercial certification for the Limiting Factor – the first time any deep submergence vehicle has been given such a safe rating by a class agency. We are so proud of the entire team here for that achievement and the recovery operation.

This was also Patrick’s first dive to the bottom of the Challenger Deep, making him the second Canadian to do so (James Cameron was first) and Jonathan is now the first German national to make the journey!

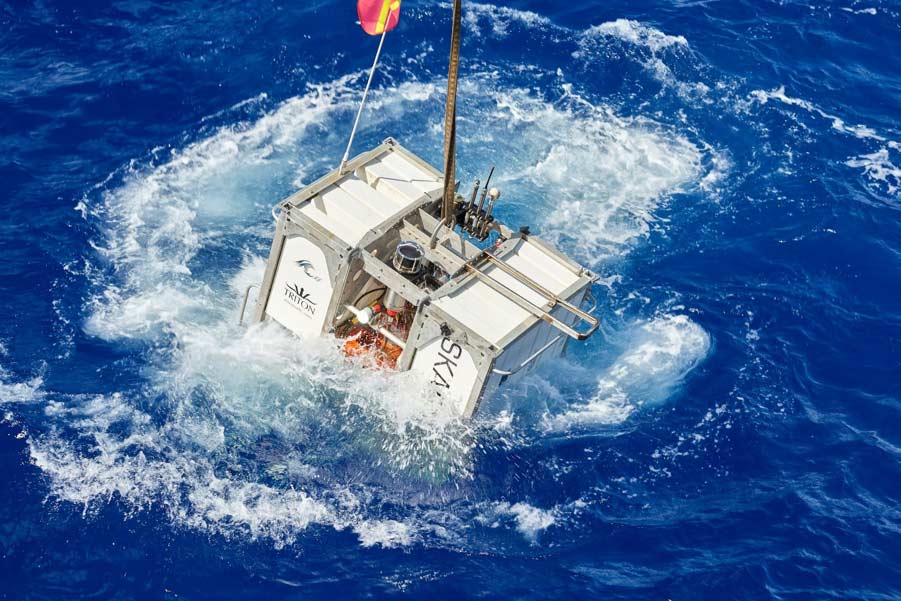

Launching the Limiting Factor on its commercial certification dive and as a side bonus, the deepest attempted marine salvage dive in history.

Celebration in the Control Room as we receive word that Skaff has been released from his captivity and is heading to the surface. I am double-high-fiving with Kelvin Magee of Triton Submarines, one of the sub’s key builders/maintainers and leader of the launch and recovery team. Rob McCallum, expedition leader, is at left.

The recovered lander “Skaff”. It spent 2.5 days on the bottom of the Challenger Deep, none the worse for wear except for some almost-completely drained batteries. He has now spent more time on the absolute bottom of the ocean than any other machine.

Left: Pilot Patrick Lahey, Triton Submarines. Second Canadian to the bottom of the Challenger Deep (after James Cameron). Right: Jonathan Struwe, DNV GL — first German national to the bottom of the Challenger Deep. This is also the deepest marine salvage crew in history.

SALVAGE DIVE PREP. We made the decision today to try to salvage our errant lander Skaff. We needed to do a dive to the bottom of the Challenger Deep anyway in order to obtain commercial-grade certification of the sub by DNV/GL with their onboard representative, Jonathan Struwe. Patrick Lahey, President of Triton submarines, the vessel’s builder, and one of the world’s best submersible pilots will pilot the sub while Jonathan accompanies him to monitor systems and help search for the lander. It made sense to let Patrick pilot the sub since he has, literally, 100x as much hours in submarines than I, and is an experienced deep-salvage submarine operator. This mission, I felt, was too important to leave in the hands of an amateur like myself.

Since we believe Skaff’s batteries to be drained since he has been on the bottom for 2.5 days, the plan is to put one lander (Closp) on the bottom as a base of navigation and conduct a square search pattern from him to find Skaff. If they do, they will try to dislodge him with the submarine’s manipulator arm. It will be difficult, since Skaff’s batteries will not be powering his camera brilliant light which provides a lot of assistance to find a lander on the surface. His strobe light should still be on, however, which could help. The team will have 4 or more hours to conduct a search and hopefully find him. They have a decent chance, we think, but this will be the deepest attempted marine salvage operation in history.

Lander Skaff at the bottom of the Challenger Deep. This picture was taken on Dive #2 by me from inside the sub. He didn’t look that stuck . . . (But you can see his metal “feet” are partially buried under the silt. It was just enough to evidently keep him pinned down.)

Discussing the potential salvage dive in the Control Room. Expedition leader Rob McCallum is in the foreground, me in the middle, Dr. Don Walsh in the background.

SECOND DIVE. Another Success.

This time it appears I got slightly deeper – by just three meters, than the last dive, to 10,925[1] meters. This was therefore the deepest dive in history, since the previous record was set by the Trieste in 1960 at 10,912 meters – according to the figure in Jacque Piccard’s book Seven Miles Down. The depth we achieved was verified by the actual pilot of the Trieste, Don Walsh, as well as a representative of DNV GL, a maritime certifying body, who checked the multiple (three) CTD data sources we used on the dive and applied the widely-accepted UNESCO conversion formula for converting pressure readings into actual depth. Everything was accounted for, so there was much celebration on top when I arrived.

But there was an unfortunate caveat to the success . . . I was able to solo pilot the Limiting Factorto the bottom of the Challenger Deep for a second time, but it appears that one of my three landers – Skaff – got stuck in the deep mud at the bottom of the trench. I was actually able to locate both him and his brother lander, Flere, during my 3+ hours on the bottom and it didn’t look that bad but evidently it was. Flere and Closp surfaced after my dive but Skaff remained on the bottom, which is very unfortunate. I was, however, able to collect a lot more video of the sea floor as well as explore the rock- and boulder-strewn southern ridge of the Deep. A bit of a bittersweet accomplishment with the missing lander, but I was also so pleased that we were able to prove the durability and capability of this submersible in making the first, repeat dive in the Challenger Deep in just 72 hours.

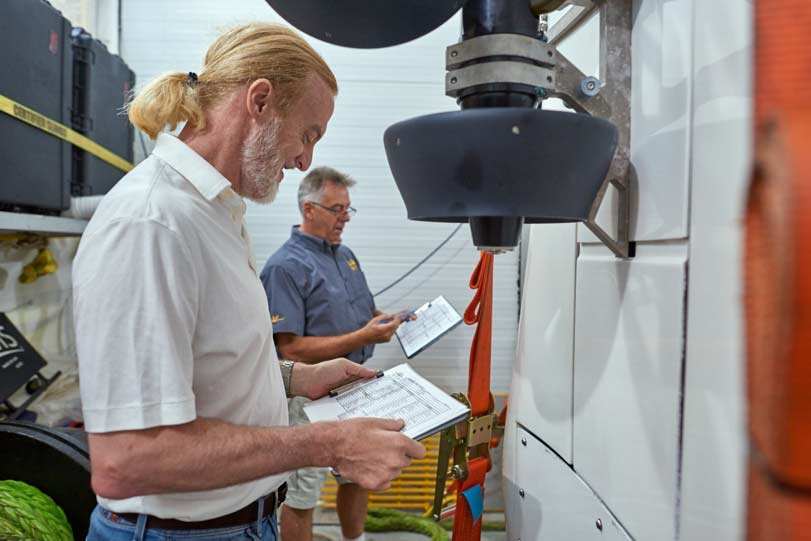

Patrick Lahey, President of Triton Submarines, and I carefully “pre-flighting” the Limiting Factor for its next dive. Even though the sub technician team executes their own checks, like good pilots we religiously check everything again personally right before a dive to help ensure a successful mission.

Boarding the Limiting Factor for the second dive.

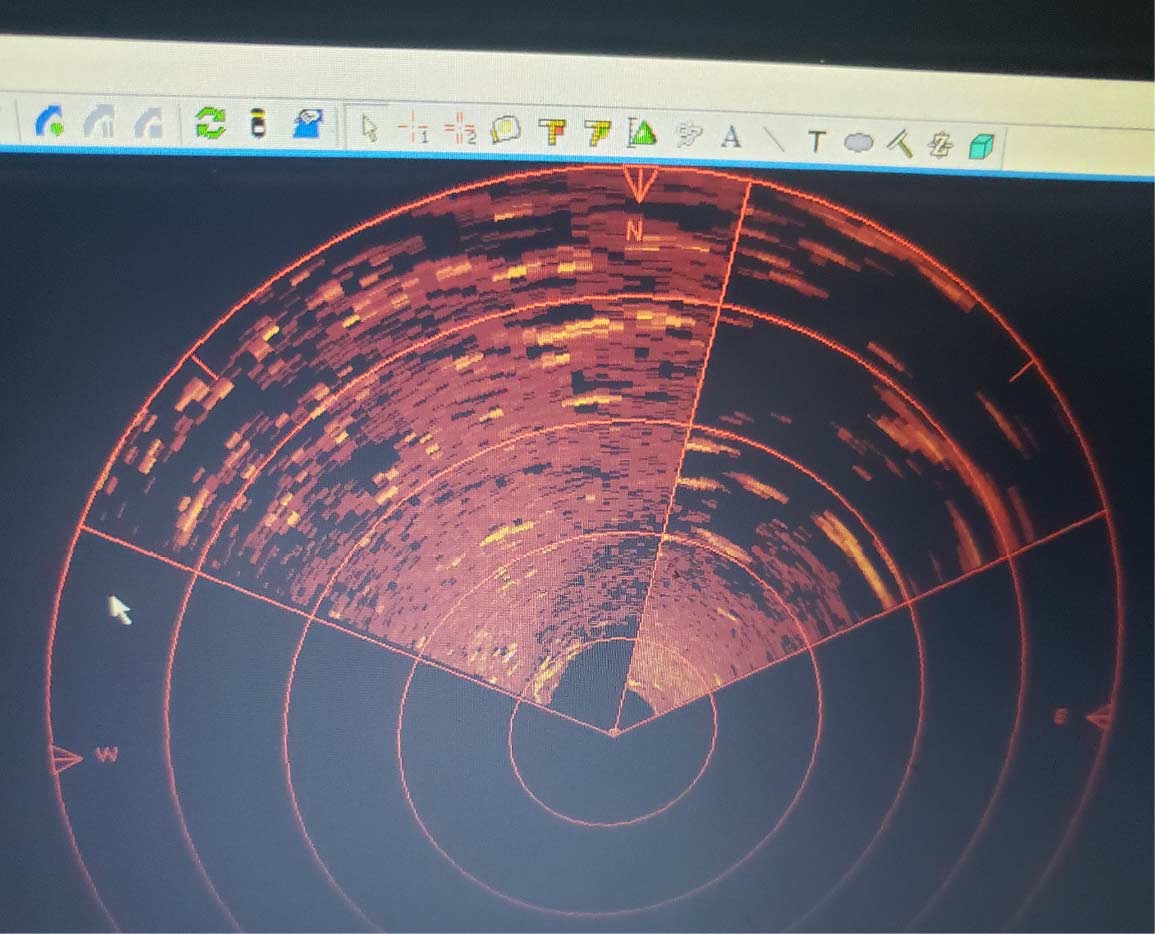

What a wall of rocks looks like on the sub’s sonar. Caution ahead when approaching the “South Wall” of the Challenger Deep. One doesn’t want to go bumping into rocks at FOD with your submarine.

The first British flag to go to the bottom of the Challenger Deep. (God Save the Queen!) . . . But also the first flag from the Principality of Monaco – Thank you Prince Albert for being such a wonderful supporter of ocean research and education!

Tim MacDonald, our Australian diver and sub technician, riding the Limiting Factor while under tow. Tim is critical to the operation since he is responsible for preparing the sub for diving and recovery when it is on the surface, as well as hooking and unhooking the sub from the DSSV Pressure Drop. (The aluminum railings on the sub are removed immediately prior to diving and put back in when the sub is recovered. They allow for more stability by the diver and the sub occupants when it is on the surface.)

MAINTENANCE PREP. The Triton team did a great job swapping out a troublesome external battery and also made some additional comfort modifications to the sub, like a second small heater. It gets quite cold in the capsule at these extreme depths, and it is nice to be able to keep the temperature in the fifties (Fahrenheit) instead of the mid-thirties by the time one is done with a dive. Certainly bearable, but less pleasant than it otherwise could be. We also troubleshooted the manipulator arm, which had a bit of “arthritis” and didn’t do quite as well as I would have liked at full depth. It appears we just needed to flush out some older, thicker, hydraulic fluid. Other small improvements were made but now we are all very confident that the sub is fully ready for action to make, for the first time, a repeat dive to the bottom of the ocean. Everyone is extremely excited.

An overhead shot of maintenance work being done on the Limiting Factor. Removing and replacing a battery can be a bit of an undertaking, but can be done on the ship. The sub was designed so it be thoroughly maintained at sea, in its air-conditioned hangar.

Another gorgeous sunset as we prepare the submarine for the second dive to the Challenger Deep.

INITIAL DEBRIEF AND MAINTENANCE. The sub team did a detailed debrief of yesterday’s dive and we identified a potential sensor issue in one of the sub’s six large, external batteries. It was giving me an intermittent fault during the dive before it lost its data connection to the capsule. Nothing really alarming, but when diving to the bottom of the Challenger Deep, 3-4 hours from the surface and with limited ability to troubleshoot issues, you like to dive with a perfect sub. It can take a full day to swap out a battery, so to give the team some time and rest, we decided to just take two days for maintenance since the weather is improving every day we are out here, which is nice. I know that I also wanted another day to rest and gear up for the next attempt.

An overhead shot of maintenance work being done on the Limiting Factor. Removing and replacing a battery can be a bit of an undertaking, but can be done on the ship. The sub was designed so it be thoroughly maintained at sea, in its air-conditioned hangar.

Regular Styrofoam cups, after they have been to the Challenger Deep. The 16,000 psi at the bottom shrinks the cups to about ½ or less of their regular size.The crew regularly hand-drew designs on cups and put them in a mesh bag outside the Limiting Factor pressure hull. Here are two of mine.

SUCCESS! I was able to solo pilot the Limiting Factor to the bottom of the Challenger Deep and make only the third dive there in history. With a lot of backup data, and certified by a DNV/GL representative onboard, we believe we dove to a new record depth of 10,925[1] meters – or 13 meters deeper than the USS Triestewent in 1960. Captain Don Walsh graciously congratulated me after I arrived back on the ship after a 12-hour dive divided into 3.5 hours each way and 4 hours on the bottom (248 minutes, to be precise). It was the longest amount of time ever on the bottom, and the second – and deepest – solo dive in the Deep. The Triton and ship team did a magnificent job with the dive and now we are working to check out the sub and get it ready for a dive the day after tomorrow! No one has ever dived the Challenger Deep twice. We hope to change that very soon.

Night recovery of the Limiting Factor after its historic dive – the third-ever to the bottom of the Challenger Deep.

Me flashing the number “four” – for four of the five deeps completed on our expedition.

Dr. Don Walsh, first sub pilot to dive to the bottom of the Challenger Deep, congratulating me after my successful solo dive. Dr. Patricia Fryer, one of the world’s leading deep-ocean researchers and a member of our science team, is at center.

Me with the ice axe that I took to the summit of Mount Everest in 2010 – and to the bottom of the Challenger Deep. It is the first axe to go to the top – and bottom – of the world. The lei (flower necklace) was kindly given to me upon returning to the surface by Dr. Fryer, who is from Hawaii, in honor of the third-ever dive to the bottom of the Challenger Deep.

LANDER OPERATIONS. Lander “Skaff” was sent down to the bottom of the Challenger Deep successfully and he (the landers are “he” but the sub and ship are “she”) provided great information for tomorrow’s dive. We were able to get good estimates of potential drift on the descent as well as likely salinity and temperature. With that, we can plan the weights to put on the submarine to make sure it doesn’t have too much or too little weight when it gets to the bottom. The other two landers were prepped as well because for the first time, we will be sending all three landers down to provide navigation and allow for potential collection of sediment and biological samples. All appears set to make what we are calling the “Big Dive” tomorrow.

Launching lander “Skaff” in the middle of the night to collect precise ocean data that helps us prepare the submarine for diving.

SHIP SONAR OPERATIONS. We arrived over the Challenger Deep today and continued to sonar the area to make sure we will try to put the sub down into the deepest point of the trench system. It appears there are three “pools” as we are calling them. Dr. Walsh dove in the far west one, but we are quite certain that there might be a deeper location – just by a bit – in the “Eastern pool.” This is where James Cameron dove during his dive but based on detailed data by our science team member Dr. Patricia Fryer, his track appears to have been slightly west of where we have observed a slightly shallower depression. We will send a lander down to the bottom tomorrow to get a “hard” confirmation of its depth and to collect baseline telemetry of currents and salinity to refine our targeting of the first dive. Everything is going very well so far.

The general topography of the Challenger Deep. It is divided into three distinct “pools” with varying maximum depths. The Trieste dive in 1960 focused on the “Western Pool” which we now know to be just slightly shallower than the “Eastern Pool.” James Cameron dove in the “Eastern Pool” but was slightly to the north and west of the deepest point according to our new Kongsberg EM124 sonar. We will be diving multiple times in the Eastern Pool.

EN ROUTE. The team is in high spirits as we sail in good weather towards the Challenger Deep. The Limiting Factorhas been tended to by some members of the Triton team since we left Indonesia, and we believe it is going to be in perfect condition for the dive. The plan is to cruise southwest from Guam to the Southern portion of the Mariana trench and reconfirm the sonar profile of the area to decide where to make the first dive – in a place where we hope is the true deepest point of the Deep. It has also been a great pleasure to meet and get to know Dr. Don Walsh (Captain, USN Ret.) during the cruise, the first person (along with Swiss engineer Jacques Piccard) to dive to the bottom of the Challenger Deep in 1960. He has been regaling the entire crew with stories of that first dive and all the challenges they faced.

IMAGE: Members of the Five Deeps Challenger Deep Team. Left to Right: Rob McCallum (Expedition Leader), Victor Vescovo (Sponsor/Chief Sub Pilot), Stuart Buckle (Ship’s Captain), Alan Jamieson (Chief Scientist), Patrick Lahey (Sub Builder/Pilot), and Dr. Don Walsh (seated).

1 We originally reported this figure as 10,928 meters. As is common practice, following an extensive review of bathymetric data, and multiple sensor recordings taken by Limiting Factor and the three landers, we have revised this figure to 10,925 meters +/- 4m.